- Sir John Woodroffe

- Born: December 15, 1865, United Kingdom

Life[edit]

Sir John George Woodroffe was the eldest son of James Tisdall Woodroffe, Advocate-General of Bengal and sometime Legal Member of the Government of India, J. P., Kt. of St. Gregory, by his wife Florence, daughter of James Hume. He was born on 15 December 1865 and was educated at Woburn Park School and University College, Oxford, where he took second classes in jurisprudence and the B.C.L. (Bachelor of Civil Law) examinations. He was called to the Bar by the Inner Temple in 1889, and in the following year was enrolled as an advocate of the Calcutta High Court. He was soon made a Fellow of the Calcutta University and appointed Tagore Law Professor. He collaborated with the late Mr. Ameer Ali in a widely used textbook Civil Procedure in British India. He was appointed Standing Counsel to the Government of India in 1902 and two years later was raised to the High Court Bench. He served thereon with competence for eighteen years and in 1915 officiated as Chief Justice. After retiring to England he was for seven years from 1923, Reader in Indian Law to the University of Oxford. He died on 18 January 1936.

Sanskrit Studies[edit]

Alongside his judicial duties he studied Sanskrit and Hindu philosophy and was especially interested in Hindu Tantra. He translated some twenty original Sanskrit texts and, under his pseudonym Arthur Avalon, published and lectured prolifically on Indian philosophy and a wide range of Yoga and Tantra topics. T.M.P. Mahadevan wrote: "By editing the original Sanskrit texts, as also by publishing essays on the different aspects of Shaktism, he showed that the religion and worship had a profound philosophy behind it, and that there was nothing irrational or obscurantist about the technique of worship it recommends."[1]

Urban (2003: p. 135) identifies Woodroffe as an apologist to a prudish society for the tantras he translated into English:

The Serpent Power and The Garland of Letters[edit]

Woodroffe's The Serpent Power – The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga, is a source for many modern Western adaptations of Kundalini yoga practice. It is a philosophically sophisticated commentary on, and translation of, the Satcakra-nirupana ("Description of and Investigation into the Six Bodily Centres") of Purnananda (dated c.AD 1550) and thePaduka-Pancaka ("Five-fold Footstool of the Guru"). The term "Serpent Power" refers to the kundalini, an energy said to be released within an individual by meditation techniques.[3]

Woodroffe's Garland of Letters expounds the "non-dual" (advaita) philosophy of Shaktism from a different starting point, the evolution of the universe from the supreme consciousness. It is a distillation of Woodroffe's understanding of the ancient Tantric texts and the philosophy. He writes: "Creation commences by an initial movement or vibration (spandana) in the Cosmic Stuff, as some Western writers call it, and which in Indian parlance is Saspanda Prakriti-Sakti. Just as the nature of Cit or the Siva aspect of Brahman[Supreme Consciousness] is rest, quiescence, so that of Prakrti [matter] is movement. Prior however to manifestation, that is during dissolution (Pralaya) of the Universe Prakrti exists in a state of equilibrated energy.... It then moves... [t]his is the first cosmic vibration (Spandana) in which the equilibrated energy is released. The approximate sound of this movement is the mantra Om."[

Mahānirvāṇatantraṃ[edit]

Woodroffe translated the Mahānirvāṇatantraṃ from the original Sanskrit into English under his nom-de-plume of Arthur Avalon: a play on the magical realm of Avalon and the young later-to-be, King Arthur, within the story-cycle of tales known generally as King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table; specifically according to Taylor (2001: p. 148), Woodroffe chose the name from the noted incomplete magnum opus, the painting 'Arthur's Sleep in Avalon' by Burne-Jones.[5] Moreover, Taylor (2001: p. 148) conveys the salience of this magical literary identity and contextualises by making reference to western esotericism, Holy grail,quest, occult secrets, initiations and the Theosophists:

Unfortunately, the most important point is not made by Taylor (2001: p. 148) and that is of the Eternal return (of "The Once and Future King") a narrative, motif and archetype that pervades the two traditions of entwined esotericism, East and West.[5][6]

The Mahānirvāṇatantraṃ is an example of a nondual tantra and the translation of this work had a profound impact on the Indologists of the early to mid 20th century. The work is notable for many reasons and importantly mentions four kinds of Avadhuta.

Tantra

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

The earliest documented use of the word "Tantra" is in the Rigveda (X.71.9).[1] Tantra[note 1] is the name given by recent scholars to a style of meditation and ritual which arose in India no later than the 5th century AD.[2] Tantra has influenced the Hindu, Bön, Buddhist, Jain and perhaps part of Sikh traditions and Silk Road transmission of Buddhismthat spread Buddhism to East and Southeast Asia.

Definitions[edit]

Several definitions of Tantra exist.

Traditional[edit]

The Tantric tradition offers various definitions of tantra. One comes from the Kāmikā-tantra:

A second, very similar to the first, comes from Swami Satyananda.

A third comes from the 10th-century Tantric scholar Rāmakaṇṭha, who belonged to the dualist school Śaiva Siddhānta:

Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar[note 2] describes a tantric individual and a tantric cult:

Scholastic[edit]

Modern scholars have defined Tantra; David Gordon White of the University of California offers the following:

Anthony Tribe, a scholar of Buddhist Tantra, offers a list of features:[9]

- Centrality of ritual, especially the worship of deities

Occult

The occult (from the Latin word occultus "clandestine, hidden, secret") is "knowledge of the hidden".[1] In common English usage, occult refers to "knowledge of theparanormal", as opposed to "knowledge of the measurable",[2] usually referred to as science. The term is sometimes taken to mean knowledge that "is meant only for certain people" or that "must be kept hidden", but for most practicing occultists it is simply the study of a deeper spiritual reality that extends beyond pure reason and the physical sciences.[3] The terms esoteric and arcane have very similar meanings, and in most contexts the three terms are interchangeable.[4][5]

It also describes a number of magical organizations or orders, the teachings and practices taught by them, and to a large body of current and historical literature and spiritual philosophy related to this subject.

Occultism[edit]

Occultism is the study of occult practices, including (but not limited to) magic, alchemy, extra-sensory perception, astrology, spiritualism, religion, and divination. Interpretation of occultism and its concepts can be found in the belief structures of philosophies and religions such as Chaos magic, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Theosophy,Wicca, Thelema and modern paganism.[6] A broad definition is offered by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke:

From the 15th to 17th century, these ideas that are alternatively described as Western esotericism, which had a revival from about 1770 onwards, due to a renewed desire for mystery, an interest in the Middle Ages and a romantic "reaction to the rationalist Enlightenment".[8] Alchemy was common among important seventeenth-century scientists, such as Isaac Newton,[9] and Gottfried Leibniz.[10] Newton was even accused of introducing occult agencies into natural science when he postulated gravity as a force capable of acting over vast distances.[11] "By the eighteenth century these unorthodox religious and philosophical concerns were well-defined as 'occult', inasmuch as they lay on the outermost fringe of accepted forms of knowledge and discourse".[8] They were, however, preserved by antiquarians and mystics.

Based on his research into the modern German occult revival (1890–1910), Goodrick-Clarke puts forward a thesis on the driving force behind occultism. Behind its many varied forms apparently lies a uniform function, "a strong desire to reconcile the findings of modern natural science with a religious view that could restore man to a position of centrality and dignity in the universe".[12] Since that time many authors have emphasized a syncretic approach by drawing parallels between different disciplines.[13]

Science and the occult[edit]

To the occultist, occultism is conceived of as the study of the inner nature of things, as opposed to the outer characteristics that are studied by science. The German philosopherArthur Schopenhauer designates this "inner nature" with the term Will, and suggests that science and mathematics are unable to penetrate beyond the relationship between one thing and another in order to explain the "inner nature" of the thing itself, independent of any external causal relationships with other "things".[14][original research?] Schopenhauer also points towards this inherently relativistic nature of mathematics and conventional science in his formulation of the "World as Will". By defining a thing solely in terms of its external relationships or effects we only find its external or explicit nature. Occultism, on the other hand, is concerned with the nature of the "thing-in-itself". This is often accomplished through direct perceptual awareness, known as mysticism.

From the scientific perspective, occultism is regarded as unscientific as it does not make use of the standard scientific method to obtain facts.

Occult qualities[edit]

Occult qualities are properties that have no rational explanation; in the Middle Ages, for example, magnetism was considered an occult quality.[15] Newton's contemporaries severely criticized his theory that gravity was effected through "action at a distance", as occult.[

Religion and the occult[edit]

Some religions and sects enthusiastically embrace occultism as an integral esoteric aspect of mystical religious experience. This attitude is common within Wicca and many other modern pagan religions. Some other religious denominations disapprove of occultism in most or all forms. They may view the occult as being anything supernatural or paranormal which is not achieved by or through God (as defined by those religious denominations), and is therefore the work of an opposing and malevolent entity. The word has negative connotations for many people, and while certain practices considered by some to be "occult" are also found within mainstream religions, in this context the term "occult" is rarely used and is sometimes substituted with "esoteric".

Christian views[edit]

Christian authorities have generally regarded occultism as heretical whenever they met this: from early Christian times, in the form of gnosticism, to late Renaissance times, in the form of various occult philosophies.[17] Though there is a Christian occult tradition that goes back at least to Renaissance times, when Marsilio Ficino developed a Christian Hermeticism and Pico della Mirandola developed a Christian form of Kabbalism,[18] mainstream institutional Christianity has always resisted occult influences, which are:[19]

- Monistic in contrast to Christian dualistic beliefs of a separation between body and spirit;

- Not monotheistic, frequently asserting a gradation of human souls between mortals and God; and

- Sometimes not even theistic in character.

Furthermore, there are heterodox branches of esoteric Christianity that practice divination, blessings, or appealing to angels for certain intervention, which they view as perfectly righteous, often supportable by gospel (for instance, claiming that the old commandment against divination was superseded by Christ's birth, and noting that the Magi used astrology to locate Bethlehem). Rosicrucianism, one of the most celebrated of Christianity's mystical offshoots, has lent aspects of its philosophy to most Christianity-based occultism since the 17th century.

Hindu views[edit]

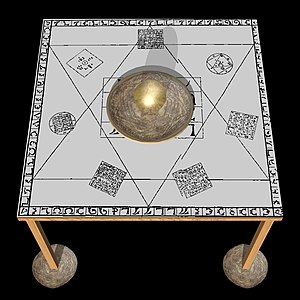

Tantra, literally meaning "formula", "method", or "way", (parallel to the Chinese Tao, which also means "the way" or "the method"), and also having the secondary meaning of "loom", "thread", or "warp and woof", is the name scholars give to a style of religious ritual and meditation that arose in medieval India no later than the fifth century CE, and which came to influence all forms of Asian religious expression to a greater or lesser degree.[20] Tantra is at the same time a method of psychoanalysis, a way of integrating the body, mind, and spirit, and a way of using the mind or will to cause change in one's external situations and circumstances, hence "magic". It includes amongst its various branches a variety of ritualistic practices ranging from visualisation exercises and the chanting of mantras to elaborate rituals. Alchemy, astrology, herbalism, yogic practices, sex magic, and trance also together form the multifaceted and multilevel nature of Tantra. Yantra, literally: "instrument" or "tool" are geometric diagrams considered to be the subtle or finer representation of the psychological or natural powers that are the deities, the proper use of which would result in the yantra becoming "activated" and infused with the particular powers and capacities of the said deity, for the practitioner or adept to put to his or her use.

Occult concepts have existed in the Vedic stream too. The Atharva Veda, representing an independent tradition markedly different from the other three Vedas, is a rich source parallel to the Vedic traditions of the Rig, Sam, and Yajur Vedas, containing detailed descriptions of various kinds of magical rituals for different results ranging from punishing enemies, to acquisition of wealth, health, long life, or a good harves

Religious Jewish views[edit]

See also: Kabbalah

In Rabbinic Judaism, an entire body of literature collectively known as Kabbalah has been dedicated to the content eventually defined by some as occult science. The Kabbalah includes the tracts named Sefer Yetzirah, the Zohar, Pardes Rimonim, and Eitz Chaim.

Although there is a popular myth that one must be a 40-year-old Jewish man, and learned in the Talmud before one is allowed to delve into Kabbalah, Chaim Vital says exactly the opposite in his introduction to Etz Chaim. There he argues that it is incumbent on everyone to learn Kabbalah—even those who are unable to understand the Talmud. Further, the father of the Lurianic School of Kabbalah, Isaac Luria (known as theAri HaKadosh, or the "Holy Lion"), was not yet 40 years old when he passed away.

Hellenic Religious Views[edit]

Followers of Hellenismos or Hellenic Reconstructionist Polytheists, reject magic and occultism on the basis that it pretends to force or compel the Gods into taking action. Also because severe laws were enacted against magic by the Athenian Assembly.

History[edit]

Name[edit]

What has become known as "Kundalini yoga" in the 20th century, after a technical term peculiar to this tradition, has otherwise been known[clarification needed] as laya yoga (लय योग), from the Sanskrit term laya"dissolution, extinction". The Sanskrit adjective kuṇḍalin means "circular, annular". It does occur as a noun for "a snake" (in the sense "coiled", as in "forming ringlets") in the 12th-century Rajatarangini chronicle (I.2).Kuṇḍa, a noun with the meaning "bowl, water-pot" is found as the name of a Naga in Mahabharata 1.4828. The feminine kuṇḍalī has the meaning of "ring, bracelet, coil (of a rope)" in Classical Sanskrit, and is used as the name of a "serpent-like" Shakti in Tantrism as early as c. the 11th century, in the Śaradatilaka.[3] This concept is adopted as kuṇḍalniī as a technical term into Hatha yoga in the 15th century and becomes widely used in the Yoga Upanishads by the 16th century.

Hatha yoga[edit]

The Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad is listed in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads. Since this canon was fixed in the year 1656, it is known that the Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad was compiled in the first half of the 17th century at the latest. The Upanishad more likely dates to the 16th century, as do other Sanskrit texts which treat kundalini as a technical term in tantric yoga, such as the Ṣaṭ-cakra-nirūpana and the Pādukā-pañcaka. These latter texts were translated in 1919 by John Woodroffe as The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga In this book, he was the first to identify "Kundalini yoga" as a particular form of Tantrik Yoga, also known as Laya Yoga.

The Yoga-Kundalini and the Yogatattva are closely related texts from the school of Hatha yoga. They both draw heavily on the Yoga Yajnavalkya (c. 13th century),[4] as does the foundational Hatha Yoga Pradipika. They are part of a tendency of syncretism combining the tradition of yoga with other schools of Hindu philosophy during the 15th and 16th centuries. The Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad itself consists of three short chapters; it begins by stating that Chitta (consciousness) is controlled by Prana, and it's controlled by moderate food, postures and Shakti-Chala (I.1-2). Verses I.3-6 explain the concepts of moderate food and concept, and verse I.7 introduces Kundalini as the name of the Shakti under discussion:

- I.7. The Sakti (mentioned above) is only Kundalini. A wise man should take it up from its place (Viz., the navel, upwards) to the middle of the eyebrows. This is called Sakti-Chala.

- I.8. In practising it, two things are necessary, Sarasvati-Chalana and the restraint of Prana (breath). Then through practice, Kundalini (which is spiral) becomes straightened."[5]

Modern reception[edit]

Swami Nigamananda (d. 1935) taught a form of laya yoga which he insisted was not part of Hatha yoga, paving the way of the emergence of "Kundalini yoga" as a distinct school of yoga.

"Kundalini Yoga" is based on the treatise Kundalini Yoga by Sivananda Saraswati, published in 1935. Swami Sivananda (1935) introduced "Kundalini yoga" as a part of Laya yoga.[clarification needed][6] Together with other currents of Hindu revivalism and Neo-Hinduism, Kundalini Yoga became popular in 1960s to 1980s western counterculture.

In 1968 Kundalini Yoga was introduced to the US by Yogi Bhajan who founded the "Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization" (3HO) as a teaching organization. While Yoga practice and philosophy is generally considered a part of Hindu culture, Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan is founded on the principles of Sikh Dharma. Although it adheres to the three pillars of Patanjali's traditional yoga system: discipline, self-awareness and self-dedication (Patanjali Yoga Sutras, II:1), Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan does not condone extremes of asceticism or renunciation. Practitioners are encouraged to marry, establish businesses, and be fully engaged in society. Rather than worshiping God, Yogi Bhajan's teachings encourage students to train their mind to experience God.[7] Yogi Bhajan sometimes referred to the Sikh lifestyle as Raja Yoga, the yoga of living detached, yet fully engaged in the world.[7]

In respect of the rigor of his teachings, Yogi Bhajan found kinship with other 20th century Sikh sadhu saints, such as Sant Baba Attar Singh, Sant Baba Nand Singh, and Bhai Randhir Singh. In the outreach of his teachings, Yogi Bhajan's contributions are unparalleled in modern times.[7]:200–208

In addition to inspiring the founding numerous yoga studios and centers of practice across the US, in 1971 Yogi Bhajan launched a pilot program for drug-treatment with two longtime heroin addicts in Washington, D.C. in 1972,[8] and opened a drug-treatment center under the name of "3HO SuperHealth" in 1973 in Tucson, Arizona.

Kundalini Yoga continues to grow in influence and popularity largely in the Americas, Europe, South Africa, Togo, Australia, and East Asia, the training of many thousands of teachers.[9] It is popularized through books and videos, charismatic teachers such as Gurmukh (yoga teacher), new research by David Shannahoff-Khalsa, Dharma Singh Khalsa, Sat Bir Singh Khalsa and others, and through the publicity accorded it by various celebs who such as Madonna (entertainer), Demi Moore, Cindy Crawford, Russell Brand, Al Pacino, David Duchovny, and Miranda Kerr who are known, or have been known, to practice it. One 2013 article in a New York wellness magazine described Kundalini Yoga as "The Ultra-Spiritual Yoga Celebs Love."[10][11]

Principles and methodology[edit]

Kundalini is the term for "a spiritual energy or life force located at the base of the spine", conceptualized as a coiled-up serpent. The practice of Kundalini yoga is supposed to arouse the sleeping Kundalini Shakti from its coiled base through the 6 chakras, and penetrate the 7th chakra, or crown. This energy is said to travel along the ida (left), pingala (right) and central, or sushumna nadi - the main channels of pranic energy in the body.[12]

Kundalini energy is technically explained as being sparked during yogic breathing when prana and apana blends at the 3rd chakra (naval center) at which point it initially drops down to the 1st and 2nd chakras before traveling up to the spine to the higher centers of the brain to activate the golden cord - the connection between the pituitary and pineal glands - and penetrate the 7 chakras.[13]

Borrowing and integrating the highest forms from many different approaches, Kundalini Yoga can be understood as a tri-fold approach of Bhakti yoga for devotion, Shakti yoga for power, and Raja yoga for mental power and control. Its purpose through the daily practice of kriyas and meditation in sadhana are described a practical technology of human consciousness for humans to achieve their total creative potential. With the practice of Kundalini Yoga one is thought able to liberate oneself from one's Karma and to realize one's Dharma (Life Purpose).[14]

Practice[edit]

The practice of kriyas and meditations in Kundalini Yoga are designed to raise complete body awareness to prepare the body, nervous system, and mind to handle the energy of Kundalini rising. The majority of the physical postures focus on navel activity, activity of the spine, and selective pressurization of body points and meridians. Breath work and the application of bandhas (3 yogic locks) aid to release, direct and control the flow of Kundalini energy from the lower centers to the higher energetic centers.[15]

Along with the many kriyas, meditations and practices of Kundalini Yoga, a simple breathing technique of alternate nostril breathing (left nostril, right nostril) is taught as a method to cleanse the nadis, or subtle channels and pathways, to help awaken Kundalini energy.[16]

Sovatsky (1998) adapts a developmental and evolutionary pe

No comments:

Post a Comment